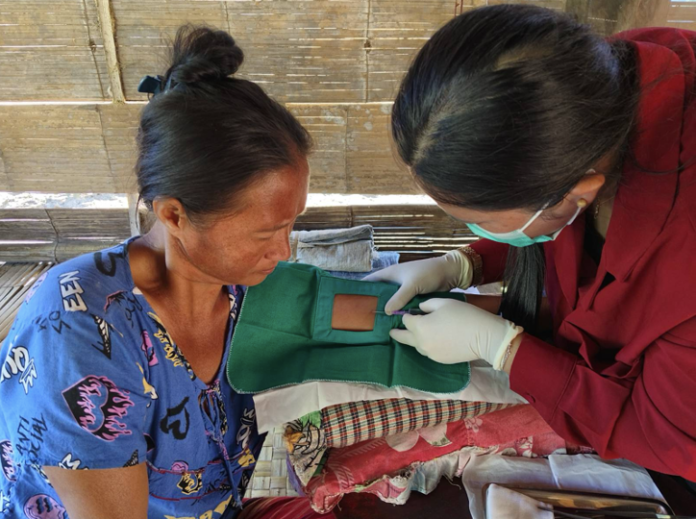

An interview with Nan Khaung, a female rural health worker, about the health conditions of people in the rural areas of Kunhein and Mongnaung Townships in southern Shan State, where access to healthcare is limited.

Rural residents in southern Shan State report that the already poor healthcare and education services have worsened further since the military coup.

People providing healthcare in villages and remote areas with limited transportation access in Kunhing and Mong Nawng Townships of southern Shan State, where there is no fighting, have had no access to health education programs and healthcare since the coup.

Shan News interviewed Nan Khaung, a female rural health worker, about the health conditions and challenges faced by the people in rural areas in southern Shan State, which no longer have access to healthcare.

Q: What is the current state of rural healthcare following the military coup?

A: Before and after the coup, there has been a high demand for female rural health workers and medicine in the remote areas of Kunhing and Mong Nawng Townships in southern Shan State. People in villages far from towns are mainly relying on traditional medicine. We cannot use motorbikes on the roads during the rainy season, as they are filled with mud in the remote areas. We have to walk to reach these villages. It’s particularly difficult for our female health staff to conduct field visits, and to transport emergency patients to the town for hospitalization. When it rains, we face landslides in the mountains. The extraction of natural resources has polluted water sources, and water is becoming increasingly scarce. Children are dying from diarrhea because the water is not clean, and they also suffer from itching. These are some of the issues I observed during my field visit.

Q: What challenges do you encounter when traveling to remote areas for medical care?

A: The main challenge I face is transportation. During the rainy season, I have to walk through flooded areas to reach patients, sometimes even using a boat. I’ve had to travel at night, putting my life at risk. The political situation here is unstable, so I fear something might happen if I visit a patient’s house late at night. But the patient’s well-being is my priority, so I can’t refuse.

The villagers don’t call us when they’re just sick. They only reach out in emergencies or critical conditions. If the situation is beyond our ability to treat, we transfer the patients to the hospital. Some villages are accessible by boat, tractor, or on foot.

Q: Both EROs and junta troops are active in Kunhing and Mong Nawng. How do you manage to work and live in this situation? Do you feel safe?

AI was threatened by armed groups. In 2019, while giving an educational talk on family planning in a rural area, an armed group came to threaten me. I was sharing information about using condoms and contraceptive implants for birth spacing, as high birth rates are common in rural areas. The armed group did not allow us to continue, claiming that we were trying to reduce their ethnic population. They insisted that people should be encouraged to have more children. We’ve been banned from conducting similar educational programs in other villages. They threatened to fine us and hold us responsible if anything happens. As a result, we have to secretly carry out health education programs for women. There are many women who die from giving birth repeatedly, so women’s health is crucial.

Q: What is the primary health issue in rural areas?

A: n rural areas, many women give birth with the assistance of midwives. Despite the availability of modern healthcare, traditional methods of childbirth are still commonly used. One of my concerns is the scissors used to cut the baby’s umbilical cord. If the scissors aren’t properly sanitized, babies can die from infections. Many babies die this way. They call us when pregnant women, assisted by untrained midwives, are unable to deliver due to weakness.

I did everything I could to assist with childbirth. If the situation wasn’t too severe, I would personally take patients to the hospital. In 2010, due to the lack of development in our region, we faced a high child mortality rate. Our region was even referred to as the ‘child grave’ because of the number of child deaths. At that time, we had to carry out many educational programs to address the issue.

Q: Finally, what suggestions would you like to provide?

A: There are many needs in our region, and health is a top priority. If possible, we would like the township health department to conduct a field study in our villages so they can observe firsthand how children and adults are struggling with poor health. Additionally, more efforts are needed to raise health awareness and provide education in remote areas.

We are unable to reach the most distant rural areas. We urge the relevant authorities to improve transportation arrangements. Better transportation would make it much easier to access these areas. Regardless of which government is in power, the health and social conditions in our region have remained the same, and the situation has only worsened now.

Sent by Shan News